Where does all the sugar come from?

In a nutshell

Most of what we eat ends up as sugar in our blood

Most of the sugar in our blood ends up as fat

The modern habit of consuming carbohydrates defies human evolution:

We consume very high levels of carbohydrates constantly

Most of those carbohydrates are in the form of bioavailable starches

I started this blog with an article that included the sorts of food I chose to restrict:

“First, I had to stop the harm. I largely stopped consuming highly processed and readily bioavailable carbohydrates (e.g., sugar, breakfast cereals, bread, rice, pasta, pastries, fruit juices, etc.). Also, fats derived from seeds (e.g., canola, corn, rapeseed, soy), high-fructose fruits (e.g., melons, bananas, oranges), and a range of starchy root vegetables (e.g. potatoes, carrots, and beets). There are strong associations between these and chronic inflammation which can lead to a range of so-called chronic diseases, which includes heart disease.”

Setting aside seed oils and industrially processed ingredients generally for the present, everything I eliminated (even fruit juices) or restricted was carbohydrate.

It’s easy at my tender age (64 biological) to encounter passing remarks and conversations about frustrations with weight loss. I hear about cutting out things like sugar and sweets. If I ask about bread, pasta, rice, fruit juice, and roast potatoes I get a smile and a shake of the head. Most of us don’t believe that those things are important in weight gain. Unfortunately, that is so far from the truth.

I wrote this in response, and will cover the following:

Why are carbohydrates fattening and how else can they be harmful?

What is a carbohydrate and why do most end up as sugar in our bodies?

We did not evolve and are not adapted to constant exposure to carbohydrates

Why are carbohydrates fattening and how else can they be harmful?

I’ll draw from a couple of previous articles for this.

Why are carbohydrates fattening?

We don’t need to eat much carbohydrate and any excess will be fattening:

Three major (macro) nutrients in our food are used as starting materials for fuel, namely carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.

Our bodies preferentially use carbohydrates and turn them into blood glucose

Blood glucose is kept not too high and not too low by the hormone insulin which sends glucose to the parts of the body where it is needed (brain, muscles, etc.)

When we eat more carbohydrates than we need immediately, our liver turns them into fat for storage and later use

How else can carbohydrates be harmful?

I covered this in some detail before so here’s a summary:

“We get glucose directly from real food such as certain vegetables, ripe fruit, and honey. We also get glucose indirectly from natural foods after we digest things like dairy and starches (e.g., root vegetables).

Problems arise when we expose ourselves continually to industrially processed ingredients… which result in very high levels of blood glucose.”

However, glucose per se is not really the problem:

“Consumption of industrially processed ingredients delivers a constantly high payload of glucose. It’s what our body does as a consequence that is the problem.

When our blood glucose is increased, our body responds by producing the hormone insulin to keep blood glucose within safe limits and to move it to where it can be used or stored for later use.

Unfortunately, the human metabolism is not adapted to cope with constant and heavy exposure to glucose. Our insulin response can’t cope and becomes the problem.”

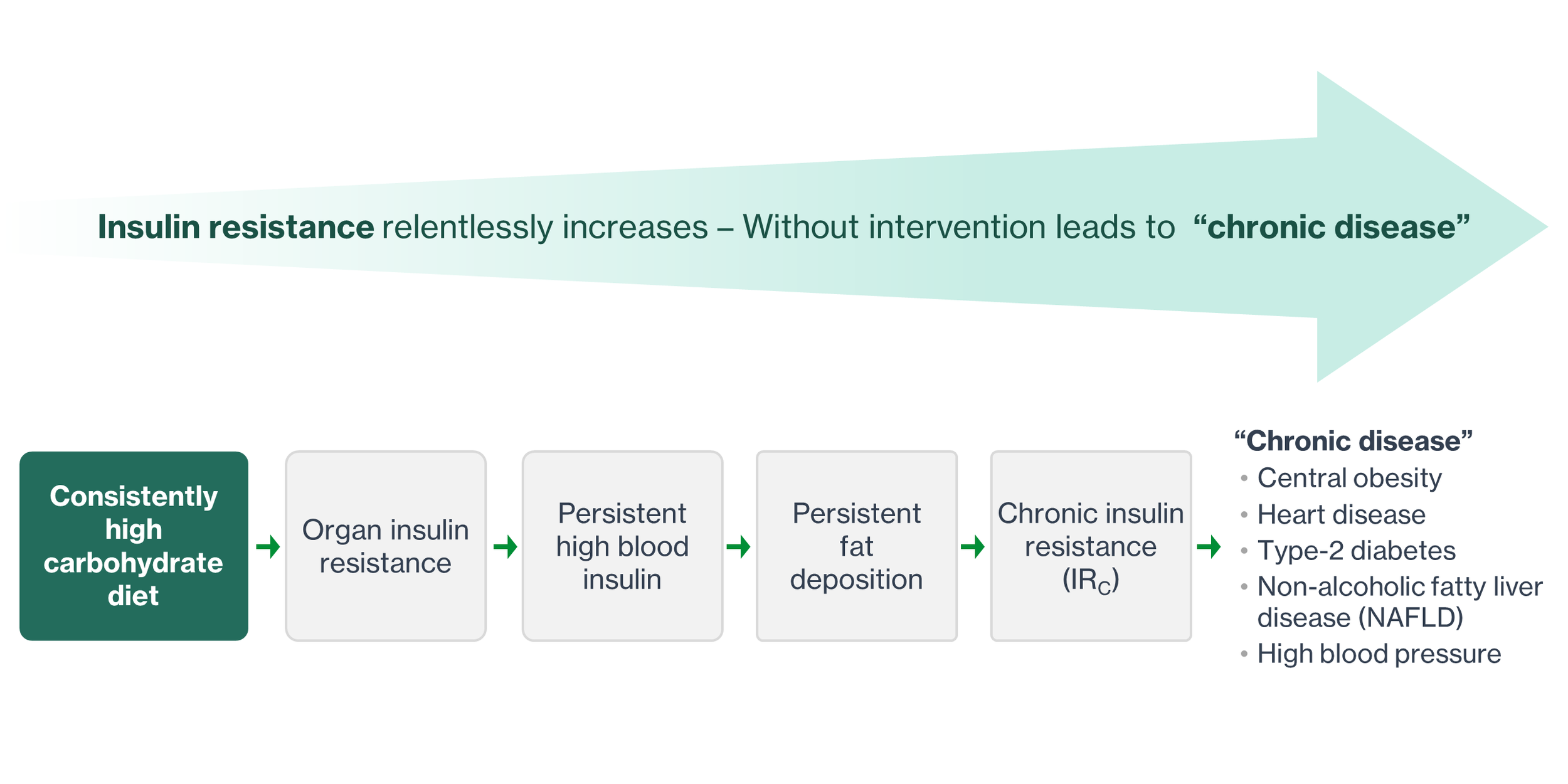

When our body is constantly producing insulin to keep our blood glucose at safe levels, our organs react and become resistant to the hormone’s message. Such insulin resistance when prolonged (chronic) creates what we refer to as chronic disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Chronic insulin resistance and raised insulin from eating high carbohydrate food leads to “chronic disease”

What is a carbohydrate?

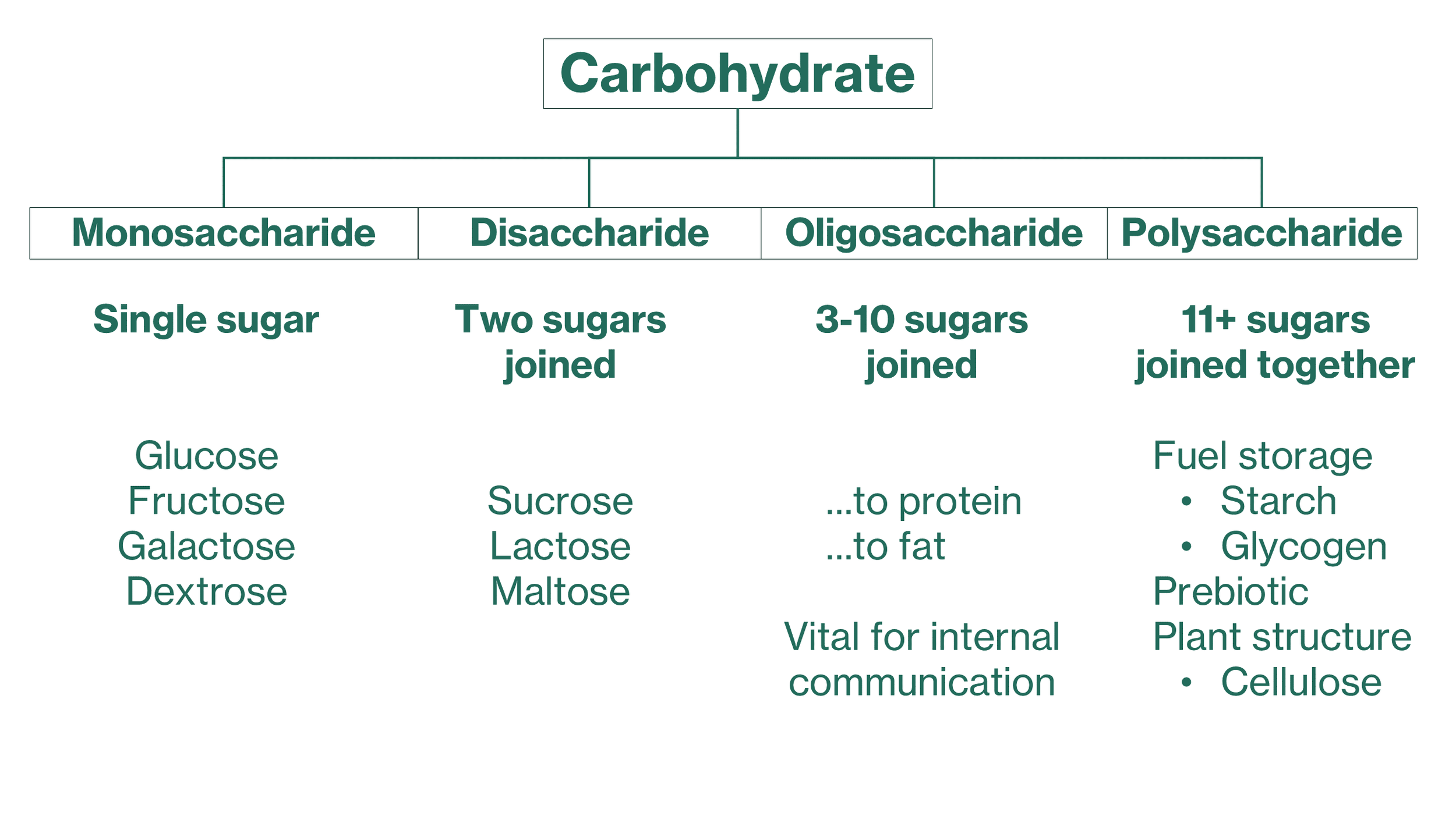

Starting with the basics, in chemistry when a word ends in -ose, it is a relatively simple sugar. Think about glucose, fructose, and lactose and how we typically think of them as blood sugar, fruit sugar, and milk sugar respectively.

Secondly, sugars exist in animals and plants with varying degrees of complexity. They range from single molecules like glucose that circulates in our blood and is vital for energy, through mid-size structures joined to proteins and fats used for communication, all the way up to much bigger structures used for energy storage (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sugars exists in nature in many forms and different levels of complexity

We also have fancy words for sugar (saccharide) and to describe the size of carbohydrates. Monosaccharide means single sugar, disaccharide means two single sugars joined together, oligosaccharide means 3-10 sugars joined together, and polysaccharide means many sugars joined together (Figure 2). Don’t ask me why we couldn’t just stick with monosugar or disugar, etc….ours is not to question why.

Why do most carbohydrates end up as sugar in our bodies?

This is where things get interesting. I think my friends believe that if they cut out sugar in tea and coffee, cut back on sweets, and beer (what a drag…!) that the job is done. Unfortunately, this ignores the enormous amount of sugar in other every-day staples.

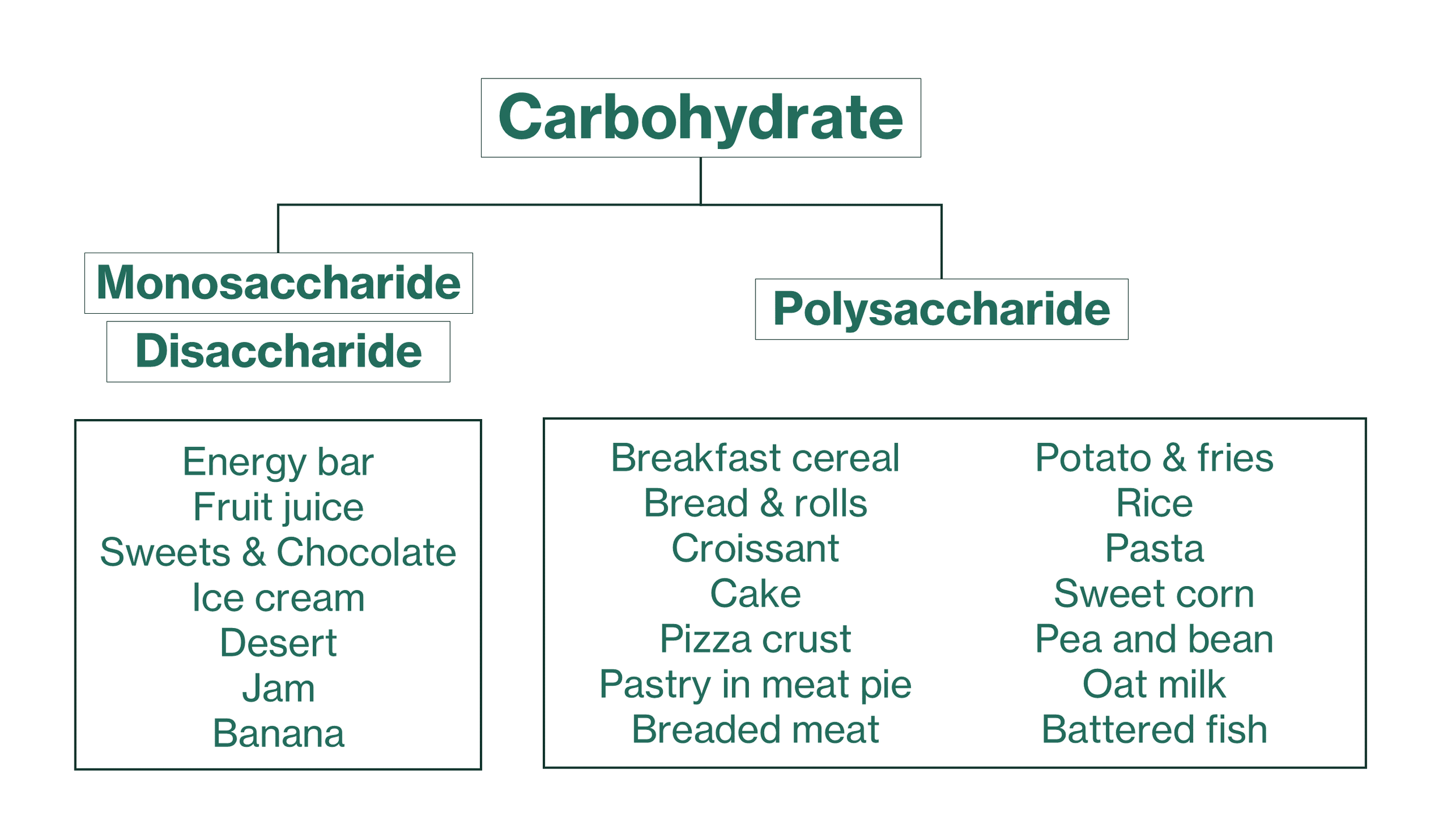

Let’s look again at the types of carbohydrate we encounter. In Figure 3, I’ve eliminated the oligosaccharides we use for communication, and show what can happen to the simple sugars and the bigger starches.

The most obvious thing is that we can use most carbohydrates as fuel. In dietary parlance, they represent calories that can be stored as fat. The remainder acts as fibre that can help feed our gut microbiome or pass through as roughage.

Figure 3: Most sugars are used by our body as fuel or stored as fat

It’s all well and good in theory, but what does all of this mean for a real life? Let’s take a look at the kinds of things we consume. Figure 4 lays out examples of the simpler sugars (mono- and disaccharides) and the more complex starches (polysaccharide).

Figure 4: The majority of sugars we eat come from starches (polysaccharide)

My friends tend to recognise and try to limit simple sugars from sweets and chocolate, ice cream, deserts, and jams. Unfortunately, I’m pretty sure they think that fruit juice is healthy when in fact it’s simple fruit sugar in a glass ready to be turned into blood glucose by our body. Similarly, high sugar fruits like bananas tend to be given a pass.

Simple sugars aside, the bigger problem rests with starches hidden in a range of dietary food-like ingredients. The biggest category is processed grains (including flour) which are found in breakfast cereal, bread and rolls, croissant, cake, pizza crust, pie pastry of all kinds, bread crumbs on meats, batter on fish, pasta, and rice. The same applies to the places that plants store their reproductive energy in potatoes, lentils, and beans. Any kind of plant “milk” (oat, almond, soy, etc) is just liquid sugar waiting to happen. Finally, whilst most of us do think of potatoes and fries as being starchy, I for one did not realise that at 15% starch, the potato pales compared to wheat (55%), corn (65%), and rice (75%).

Unless I’ve sent you into a numbed coma of jargon overload (which I’m told can happen), you’ll be asking yourself “…if blood glucose driving up insulin is the problem, why are starches an issue…?”. The answer to that lies in what starch is made of and how fiendishly clever our body handles it. Consider Figure 5.

Figure 5: Starchy food is broken down by our body into glucose

The diagram in Figure 5 simply shows that starch is composed of the simple sugar, glucose joined together. In nature, starches are composed of thousands of glucose sugars. When we digest starches they are broken down into their constituents and our blood is flooded with glucose. As blood glucose rises sharply it has to be controlled with insulin. When we consume starches all day and every day, our insulin is constantantly elevated and we run the risk of obesity and other problems shown in Figure 1.

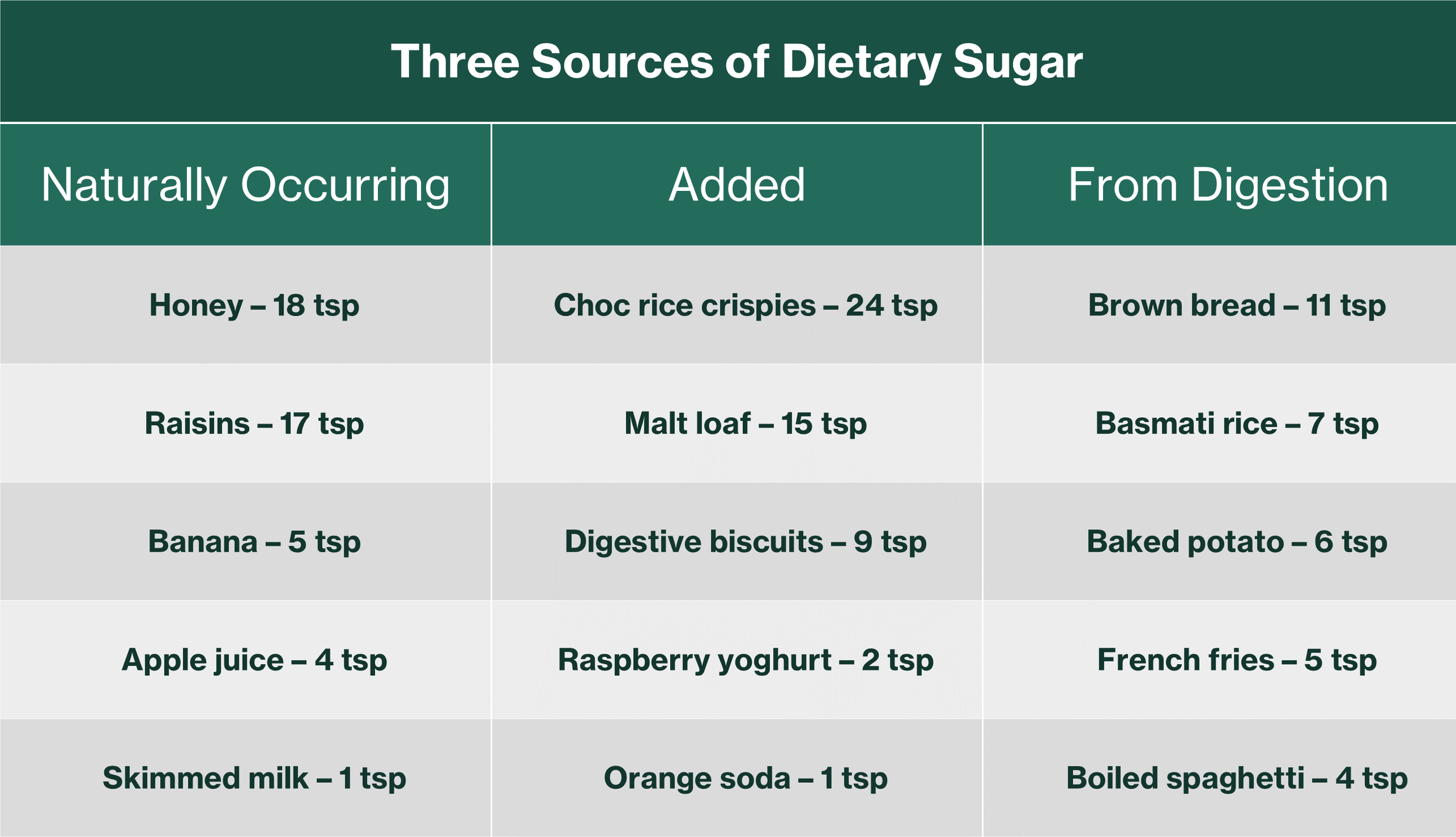

For more context, take a look at Dr. David Unwin’s work where he has converted everyday food into teaspoons of table sugar. His wife Jen Unwin has summarised some of his work in her book [1] which I’ve reproduced in Table 1.

Table 1: Table-sugar equivalent of various types of food

Human evolutionary exposure to sugar

Our species evolved in a world where animal meats (including seafood) are the most nutritious:

“Humans have lived a hunter-gatherer life for 99.6% of the past 2.5MM years of our existence. In that time we have always eaten a range of plant- and animal based foods but their relative proportions have varied over time … and place... Our animal-based diet peaked around 2MM years ago when we were considered apex carnivores getting more than 70% of our diet from large animals. Over time whilst the the size of our prey declined most of our ancestors continued to hunt and consume largely a meat-based diet. Around 10 thousand years ago, we began to domesticate plants and animals for what we now consider agriculture...”

As their meat-heavy diet was replaced with more and more carbohydrates, humans became smaller and, most recently, much sicker. I’ve previously described how this happened with the switch from hunter-gatherer to grain-based agriculture, introduction of the first industrially processed food ingredients in Victorian times, and the twentieth century explosion of industrially processed food-like ingredients.

Carbohydrates I eat

I eat a range of meats with various types of carbohydrates. The latter include above-ground vegetables (cruciferous, snap peas, runner beans, etc.), root vegetables in winter (mostly carrots, celeriac, radishes, squashes, turnips, etc.), berries and apples. I’ve included a useful graphic in Figure 6.

Figure 6: A useful graphic to separate healthy from unhealthy carbohydrates

Summary

Most of us living a modern lifestyle consume an enormous carbohydrate load every day and all day as can be seen from Figure 4 and Table 1. The majority of those carbohydrates are rapidly turned into glucose as we see from Figure 5. This rapid and prolonged conversion of starch into glucose and subsequent metabolism increases our likelihood of getting obese and suffering from other so-called chronic diseases (Figure 1).

The solution is simple…limit industrially processed, and high starch carbohydrates.

References

Unwin, J. (2021) Fork in the Road: A Hopeful Guide to Food Freedom. FITR Publishing