Nature - it is beautiful, and we know why

In a nutshell

Nature is beautiful in ways that we can recognise and describe

We can mimic and bring nature’s beauty into our busy lives

Nothing beats getting out and surrounding ourselves with the natural world

I spend a lot of time in nature, sometimes actively by biking, kayaking, hiking, or gardening. Recently I’ve been starting my day by sitting in the garden just looking at what’s going on around me.

I always find my time in nature visually attractive. The little reading into the subject I’ve done suggests that fractals may be the reason.

I’ll briefly cover three topics and then show lots of pictures (the real reason I’m writing this).

What are fractals

Fractals in nature

What happens when we use fractals, and what happens when we don’t

Fractals

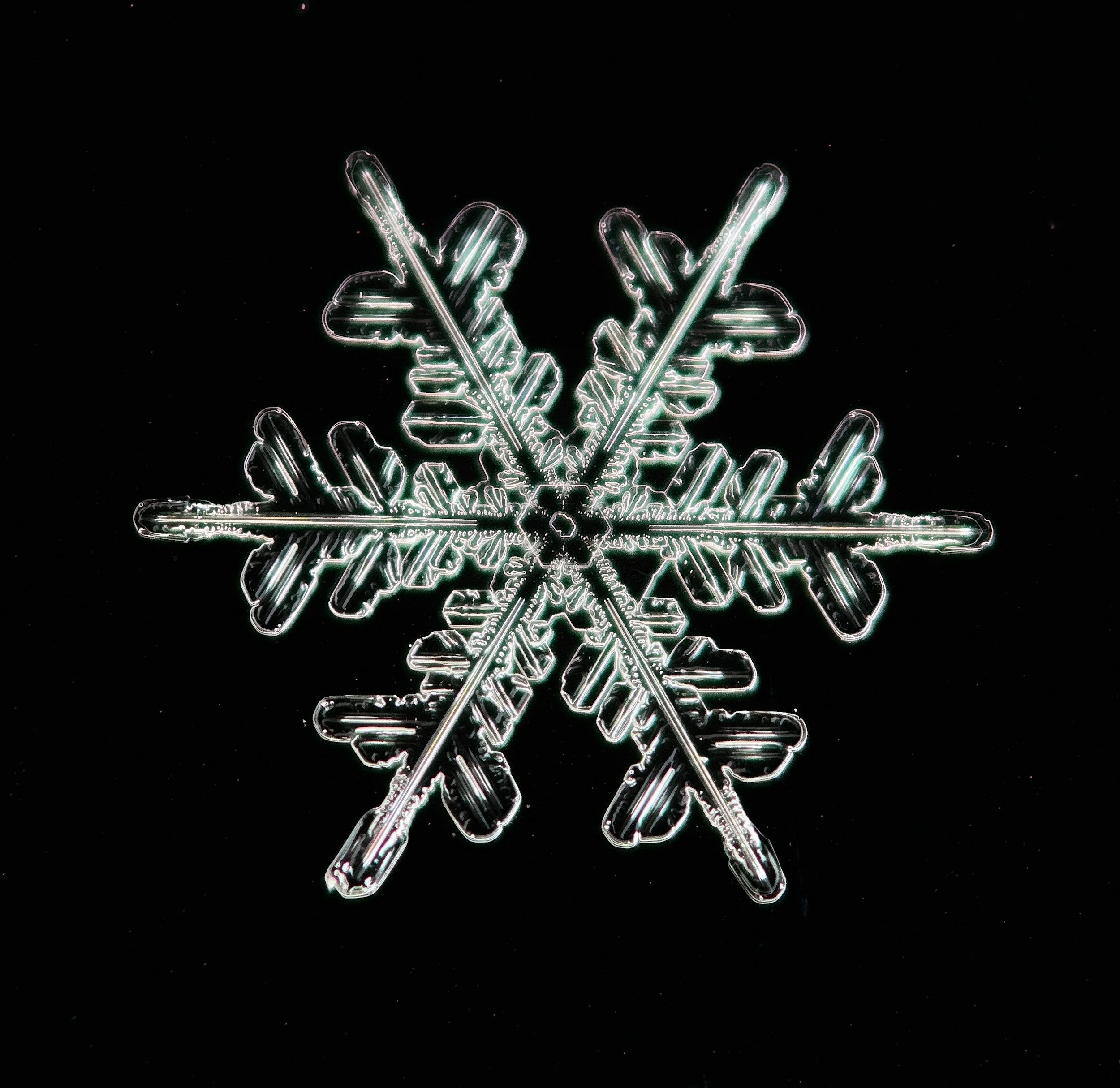

Fractals are repeating patterns that create very complex shapes. The most commonly known fractal image is probably that of the snowflake (Figure 1). As well as being rich in structure, fractals have also been shown to possess instantaneous and substantial aesthetic appeal [1]. What’s more, it has been demonstrated that an initial, unconscious positive response to fractals is universal amongst people. Beauty is not, after all, in the eye of the beholder [2].

Figure 1: Snowflake showing repeating patterns that result in a complex and attractive form

Fractals in nature

Fractals are ubiquitous in nature and can be seen in plants, forests, clouds, trees, mountain-scapes, cauliflowers, and fern leaves (Figures 2-4).

Figure 2: An attractive natural pattern made up of shapes that repeat through layers of different sizes

Figure 3: Repeating patterns are obvious in the foreground “tree” but also in the more distant live forms

Figure 4: Repeating, complex patterns in the rocks, the river water, and the background Scots Pine forest create a rich, visually appealing living environment

What happens when we use fractals, and what happens when we don’t?

People bring natural beauty into their lives in many forms. House plants (Figure 1) represent an obvious example of how we surround ourselves with natural beauty domestically. We also create clothing from natural fibres that are inherently complex and appealing (Figure 5). This was done in a much grander scale in Europe where the beauty of fractals was incorporated in the great gothic cathedrals (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Traditional clothing made of natural fibres contain the repetitive structure of the knitted garment plus the inherent complexity within micro-structure of the material itself

Figure 6: The Duomo in Milan exhibits classic use of visually appealing fractal repetition. Clouds in the background provide the same beauty, albeit differently

When we ignore the source of nature’s beauty, an odd thing happens…we create ugly structures. Modern architecture, for example, can suffer in this regard. Figure 7 shows what happens when we fail to use natural materials with their inherent visual appeal and compound the mistake with design that also lacks complexity. This sort of thing gives “man-made” a bad rap. Such modern design is an example of beauty lost by commission (by creating something that didn’t follow the basic principles of how we find things visually attractive).

Figure 7: Examples of modern architecture devoid of fractal beauty. Even the clouds and the rippling water can’t rescue this scene

Beauty can also be lost by omission. Consider again Figure 3. The foreground contains heather and tall grasses but no bushes or young trees. It thus lacks the diversity and complexity we’d expect to see in a natural scene. The same goes for the background where there are not even trees to be seen. Look again at Figure 4 where the same is true on the hill behind the Scots Pine forest. Sadly, in Scotland where large predators were lost many years ago, our landscape bears the hallmarks of mis-management. Herbivore (e.g., sheep, deer, hare) numbers have not been controlled and this has resulted in widespread over-grazing with the result that forests can’t rejuvenate and we have lost much of our landscapes’ natural beauty.

Let’s end on a positive note. Figure 8 reminds us where we came from and how we can return there when time allows.

Figure 8: Mountain biking in Glen Quoich towards one of the ancient Scots Pine forest remnants in the Forest of Mar

References

Robles, K.E., Liaw, N.A., Taylor, R.P. et al. A shared fractal aesthetic across development. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7, 158 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00648-y

Brielmann, A.A.; Buras, N.H.; Salingaros, N.A.; Taylor, R.P. What Happens in Your Brain When You Walk Down the Street? Implications of Architectural Proportions, Biophilia, and Fractal Geometry for Urban Science. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6010003